There are estimated to be 200 million stamp collectors in the world.

Just why do so many of us develop passions for the pointless?

Last week’s Investors Chronicle ran a short page-stuffer on the investment case for buying rare postal stamps in which it was mentioned that those in the philatelic know estimate there to be around 200 million stamp collectors in the world.

Two hundred million.

Or to put it another way around 1 in 35 members of the human race.

Man, that’s an awful lot of anorak sales!

And yes, perhaps I’m biased. I’m one of those people who struggles to expend effort on pointless activities (which may well account for the infrequency of my blogging) so this seems to me a rather scary number of geeks bearding their way through the tat-marts, auctions and car boot sales of this world hunting for little bits of sticky paper to assimilate into their worldly goods.

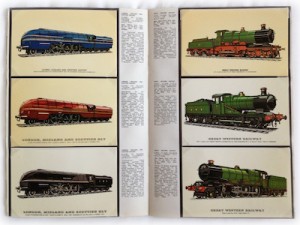

And that’s just the stamp collectors. What about the millions spending their lives passionately hunting down porcelain figurines, painted plates, baseball cards, film memorabilia, action figures, teddy-bears, dolls and other assorted gewgaws? To say nothing of the train spotters and twitchers.

And therefore, for those pondering people watchers amongst us, there is something interesting about these people. Why do they do it? Why do so many people collect useless things? Why do people so passionately pursue the patently pointless? I mean, with so many of them doing it, there has to be an explanation.

Doesn’t there?

The Squirrel Theory

If we accept the premise that most common human behaviour is driven by instincts honed by millennia of evolution for the express purpose of ensuring our survival and procreation, then to explain away a passion for the pointless we’re probably looking for a mis-firing instinct.

Hoarding seems like a credible candidate for this. In the leaner and harsher times of our ancient past acquiring stores could be both the difference between living and dying and – as a show of our wealth and industry – the difference between a shag and another night’s toll on the wrist.

Surely then we have an evolved propensity to hoard, born of the need to secure food, water, warmth, tools and so on. We might question how such an instinct could be misdirected to the acquisition of pointless artefacts but that instinct evolved during times far less abundant in pointless things for us to hoard so we needn’t have evolved too much discrimination. It’s also possible we’d ascribe a value to rarity in the items we hoard simply because they’d be harder to find if and when we needed them. Throw in the potential benefits of acquiring things of beauty as a show of worth that could well be of use in attracting and securing a mate and it looks like we might have a reasonable candidate.

But it doesn’t feel like a perfect fit to me. After all, if we’re lumping the stamp collectors and the train spotters together, it hardly covers the latter – or if it does it is quite a leap for a misfiring instinct to take.

The Completer/Finisher Theory

Survival of the fittest isn’t all about the individual, it’s also about the social group we operate in. One of the reasons we have evolved individuality is that a mixture of personality traits and innate skills makes for a richer, better, more successful social group. We’re stronger together.

The Belbin Team Roles test, a popular choice for unimaginative team-building corporate jollies, identifies nine team roles that individuals fit into, a combination of which makes for a successful team balance. In the Belbin test a Completer/Finisher is one with a passion for detail, accuracy and for the thorough completion of tasks.

The Social Theory

As a man who shamelessly admits to a total lack of interest in spectator sport I stand amongst a small and lonely minority of men. But it’s not as small a minority as the column inches dedicated to soccer and such might lead you to believe. Liberated by being in the company of one who shamelessly shuns spectator sports a fair few mates have, down the years, ‘fessed up to being merely sham sports fans. Pick any social situation from chatting with a cabbie through to impressing a hiring manager, in man-land being able to talk sports is the safest ground you can be on. Even if you don’t have passion for the sport itself knowing about it serves your passion for society and success.

Sports socially connect us. Almost everything we do has the potential to socially connect us. In The God Delusion Richard Dawkins writes of the social aspects of religion with reference to those who have no particular belief in the faith they practice but who find a cultural identity and compatible community through belonging to that religion.

In modern life socialising may itself seem a rather idle pastime but historically our being connected to a community of the right people could well be the difference between life and death. It makes sense that we have a strong instinct to seek out compatible social connections by any means available to us, and our hobbies and interests reveal aspects of our character and personality that act almost like a contact ad for the people we meet.

The Passer Over Perilous Ways Theory

While I like to find clear, singular explanations for all aspects of human behaviour, perhaps it is the almost definitive irrelevance of our pastimes that makes the instincts behind them so hard to pin down. Why, after all, should idle pleasures have a survival of the fittest explanation? Maybe the explanation is all of the above possibilities and several others too. Where our instincts are most weakly directed, tickling any of them just a touch is probably enough to make us pick a hole.

And, of course, in a world that blesses us with so much idle time, you’ve got to spend it doing something.